Every parent who has loved a child knows the extent to which our children become a part of us. It’s a powerful thing. And it’s certainly something that all kinds of parents experience: adoptive parents, foster parents, biological parents. These little humans that pass through our lives, live in our hearts, and take a piece of us along with them every time they go out into the world.

Every parent who has loved a child knows the extent to which our children become a part of us. It’s a powerful thing. And it’s certainly something that all kinds of parents experience: adoptive parents, foster parents, biological parents. These little humans that pass through our lives, live in our hearts, and take a piece of us along with them every time they go out into the world.

Yesterday, I found the most amazing biological scientific study from Arizona State University that proves this. It demonstrates how fetal cells stay in a mother’s body long after the baby is born[i] – some, for her lifetime. They migrate to her heart, liver, and even her brain. In some cases they are helpful to her health. In other cases, they are apparently not so helpful.

I’m no scientist but I’m struck by this metaphor and by the ways our physiology perfectly parallels the way we experience both ourselves and our relationship with others. We are, after all, whole creatures – but when the parallels show up like this, it’s just striking.

And this is most certainly a metaphor that is apt for all kinds of parents and for both women and men.

Parenting is not-to-be-idealized. It’s hard work and sometimes children can tear out our hearts. When my daughter was an infant she cried. She cried a lot. And for no apparent reason. It was hard, and I felt completely inept. When my son came along, he would just not sleep. Again, it was hard, and again, I felt completely inept. Sometimes the rejection of a small child or that teenage eye-roll can cut a little deeply. It turns out that fetal cells can also be damaging. They are linked with autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid cancer, Grave’s disease, morning sickness, postpartum depression, and even early-onset menopause.

But it’s worth it. When we love deeply, we can be hurt deeply and the love for a child is fierce.

And on the other hand, parenting is also the most joyous, compelling, amazing journey as well. Sometimes my love for my children comes over me like a wave, completely overwhelming me. It is palpable and I can feel it through my whole self, down to my toes. I know other parents experience this too, because we’ve talked about it. Fetal cells mirror this too. They contribute to wound healing. For example, their presence at wound sites (caesarian incisions are an example) points to this active role in healing. Their presence in the breast implicates them in healthy development and lactation[ii]. And they contribute to neural pathways in the brain for positive emotions and behavior affecting love and bonding for years to come.

It’s complex, really complex, because the cells flow in all directions. Maternal cells also pass to fetuses.

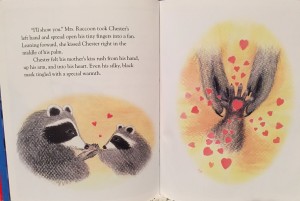

One of our family’s favorite books is called The Kissing Hand by Audrey Penn[iii]. It’s about a mother raccoon who is reassuring her son Chester who is starting school. She kisses his hand “Chester felt his mother’s kiss rush from his hand, up his arm, and into his heart. Even his silky, black mask tingled with special warmth.” “Now,” Mrs. Raccoon tells Chester, “whenever you feel lonely…press your hand to your cheek…and that very kiss will jump to your face and fill you with toasty warm thoughts…and when you open your hand and wash your food, I promise the kiss will stick.” We read The Kissing Hand to our children as they were starting school. I could rarely get through it without tearing up (because I’m emotional like that, but also) because it spoke to me about how we become a part of each other and about how our deep love migrates into our children and they migrate into us.

And here’s one more thing about fetal cells. The fetal cells present in the mother’s body from one child, also pass to new fetuses. In addition, fetal cells from the subsequent children passing to the mother’s body can compete for resources there. We’re in territory here that is way above my scientific acumen, but with my half-a-thimble full of knowledge on this topic[iv], the metaphors for relationships seem rich.

- We are all incredibly connected.

- We affect each other deeply – whether or not we are consciously aware of just how deeply – and for better and for worse.

- We invite our children into our lives and we are never the same.

Lots of people have brought children into their lives in all kinds of ways, and these children are as much a part of them as any biological parent’s children. Valerie and her husband adopted their son. M and her husband adopted their daughter. Art and Tonya fostered and then adopted their son and daughter, in addition to parenting their two older daughters. My cousin Andy and his wife Annie just brought their new son Theo home from China and he is welcomed by them and their two older daughters (this is their blog honoring Theo and their journey). Each of these parents are very (very) connected to their children (as are their siblings to new siblings).

We invite children into our hearts and our lives and we are never the same. We are humans sharing this lifetime together. Sometimes it’s really tough and it hurts. Sometimes it’s really rewarding. It’s always an amazing and awe-inspiring thing, this biology of ours and this parenting we do.

These are the children who live in Terry’s and my hearts.

~~~

[i] This is called fetal microchimerism and this is the link to the study.

[ii] The relationship to the breast is complex. Lower abundance of fetal cells has been found in situations where breast cancer is present, but higher abundance of fetal cells has been identified when the breast cancer occurs in the years immediately following pregnancy.

[iii] The Kissing Hand by Audrey Penn with illustrations by Ruth E. Harper and Nancy M. Leak. Published by Child & Family Press in Washington D.C. in 1993.

[iv] The implications for this fetal microchimerism are exciting. There may be positive applications for treatment of poor lactation, wound healing, tumor reduction, or psychological disorders.